What do we want?

For us, “reclaim and remain” means that we must focus on plans for the future. For this work, we review collected data and work towards advocating for solutions to enable Black Oaklanders to reclaim and remain in their place in the Town. Specifically, this portion of the project is devoted to locating, analyzing, and even playing with relevant articulations of future. By this we mean visions for a Black future in Oakland, as well as various political constructions for an alternative state of housing in the region, and even hopes held for the individual lives of tenants who are seeking relief from the persistent struggles of insecure housing. The primary motivation for our future-oriented work is to seek out and wrestle with these various expressions of an otherwise that are most relevant to the lives of Black Oaklanders, to understand how they stand together and where they may be at odds.

To do so, we facilitated a series of workshops that guided participants through “futuring” work, wherein they are asked to engage their imaginations and think through what possibilities might exist for their lives in a world without landlords and without rent; what version of themselves might be released, who might they become were they to permanently secure stable housing? This led to individual and collective imagining sessions made up workshops devoted to sharing these visions and thinking through their meanings and relevance to the ongoing fight for Black Oakland.

“Reclaim and Remain” is devoted to locating, analyzing, and even playing with relevant articulations of the future. By this we mean visions for a Black future in Oakland, as well as various political constructions for an alternative state of housing in the region, and even hopes held for the individual lives of tenants who are seeking relief from the constant struggles of insecure housing.

Such future visions are sometimes explicit and sometimes implied; they may reside in the text of Senate bills and local ordinances, or lost somewhere in the private prayers or rushed testimonies of the tired and displaced. And yet, some articulations of the future may have yet to find a venue for expression. Therefore, the primary motivation for our future-oriented work is to seek out and wrestle with these various expressions of an otherwise that are most relevant to the lives of Black Oaklanders, to understand how they stand together and where they may be at odds.

We facilitate a series of workshops that guide participants through “futuring” work, where they are asked to engage their imaginations and think through: what possibilities might exist for your lives in a world without landlords and without rent? What version of yourself might be released? Who might you become were you to permanently secure stable housing?

The workshops are devoted to sharing these visions and thinking through their meanings and relevance to the ongoing fight for Black Oakland.

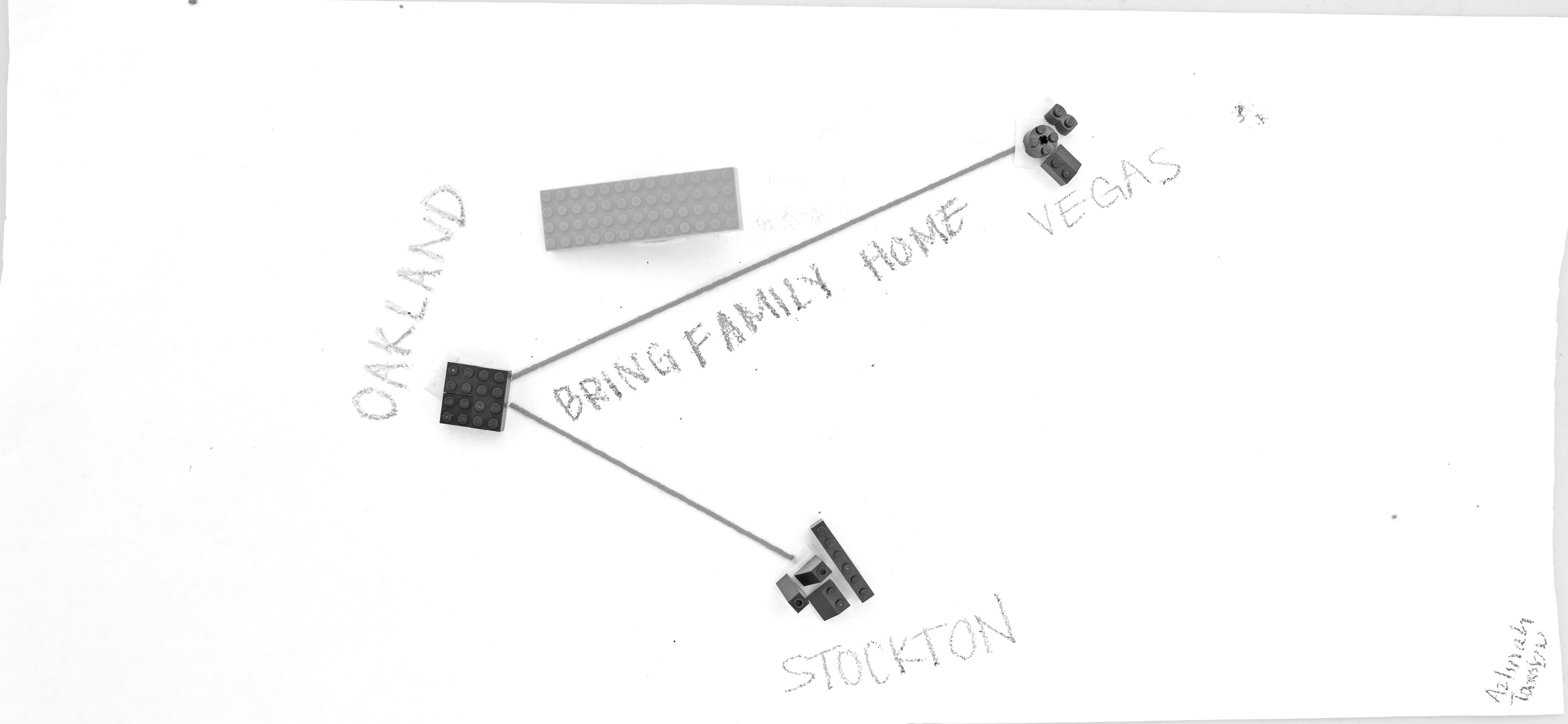

“Hyphy Rail”: The “Hyphy Rail” is imagined as an affordable, high-speed train that could rejoin families who were disconnected due to gentrification and housing financialization.

Between the 1990s and early 2000s, Black and Latinx residents were given access to housing credit through subprime loans (loans with lower credit rating). Subprime loans were used by banks as a way to generate more income and not take on as much risk. Until the 1990s, racially marginalized groups were systematically excluded from participating in mortgage-finance because of the ways banks employed redlining and discrimination. The problem emerged when the loans were starting to be used to cover the gap between people’s income and the price of the house. So, that means the loans became inherently speculative, not actually based on the value of the property. By 2007, financial losses Black and Latinx borrowers took via high interest rates and risky terms pushed them into foreclosure. Between 2007-201, over 10,000 homes in Oakland were foreclosed, mostly in East and West Oakland. Already hampered by the devastating impact of gentrification, lower income Black and Latinx families were forced to move away from Oakland to as far away as Stockton and Las Vegas.

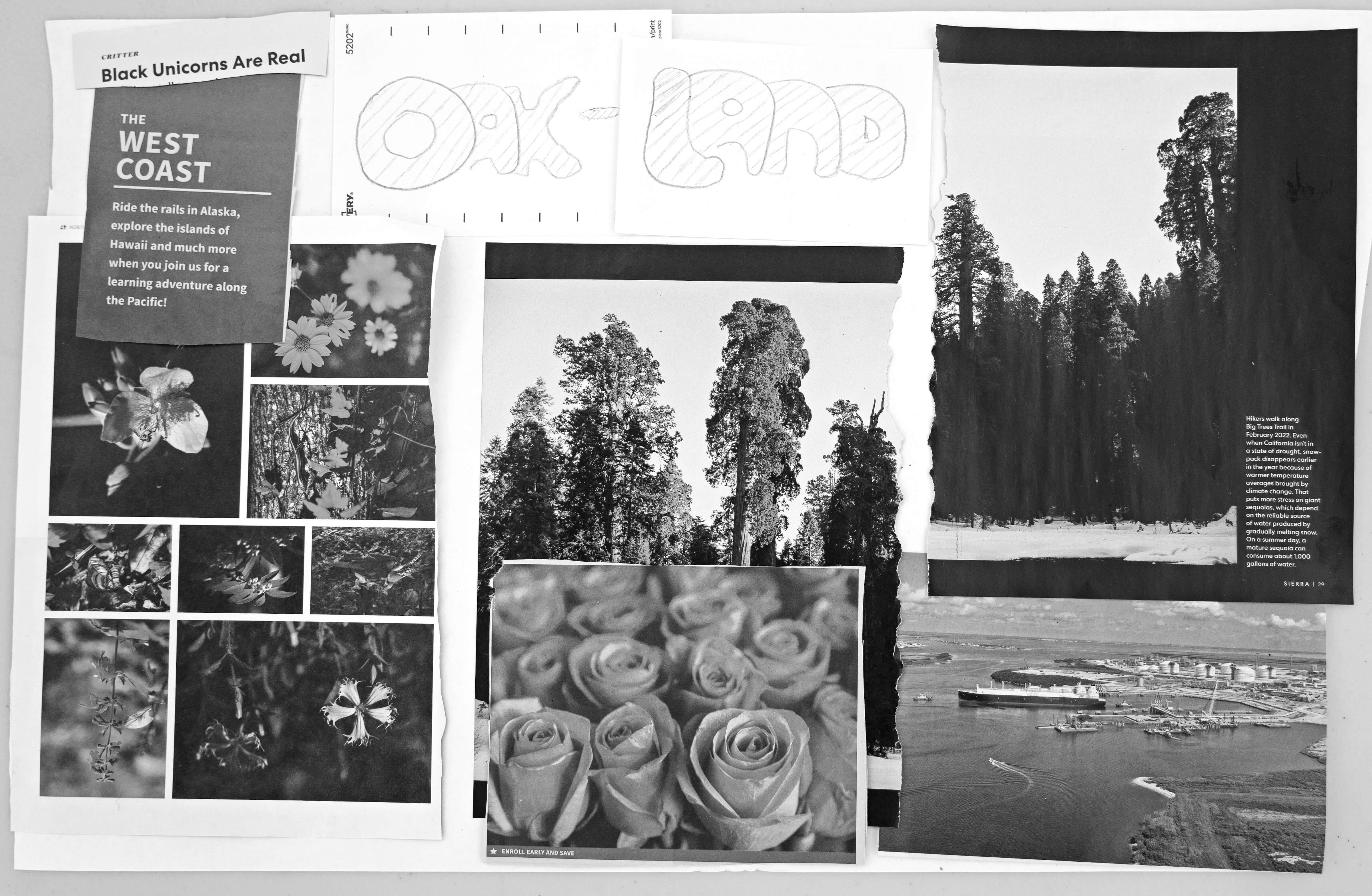

“Black Unicorns are Real”: This workshop participant reflected on her days living in Oakland in the 1970s, when Oakland was an ideal place for visiting lush green spaces and relaxing with family members at the park, including Lake Merritt. For her future Oakland, she imagines Oakland as a “Black Unicorn” haven, where Black residents experience safe passage and leisure at well-maintained parks and open spaces.

From the late 20th to early 21st century, the lake and its surrounding streets were a popular place for Black people to informally gather and socialize on Sundays. Even after Black people started to move to the outlying suburbs, they would return to the lake on Sundays after church. And yet, even this reclamation of nostalgia and community has been under threat with the increasing presence of white gentrifiers policing the space and the heavily regulated, managed, and policed Black recreational (and entrepreneurial) activities. Often thought to be man-made, Lake Merritt, nicknamed “the Jewel of Oakland,” is a 10,000-year-old tidal lagoon connected to the Pacific Ocean. Once a place where Ohlone and Miwok Indians fished, hunted, and gathered food, it was declared the country’s first wildlife refuge in 1870. In recent history, it has become not only a refuge for some of the rarest flora and fauna but also to Black Oaklanders who have regularly gathered around “The Lake” to build community and fellowship. Made notorious as the site of the “BBQ Becky” incident and the “Jogger Joe” incident, in which a white resident was seen throwing away the belongings of a Black homeless man residing under the Lake Merritt Pergola, these encounters and confrontations around the lake reflect the city’s contestation over race, space, and belonging. The impact of gentrification (rising rents, property values, and new construction in the region) has led to radical changes to the Lake’s constitution.